But what exactly is the reason why Failure Mode and Effects Analysis, has found its way into almost every QM manual, but sometimes plays only a minor role in operational practice? Well, as is often the case with really good QM methods, FMEAs quickly become victims of their own success. This is because the more effectively, potential sources of error are identified and closed with suitable countermeasures, the less frequently the quality defects associated with the risks occur in actual operation. With this in mind, it is essential to be able to demonstrate exactly what deficiencies have been identified in product and process design, how critical these weaknesses are, and what precautions have been taken to adequately eliminate the resulting risks.

Only by measuring success in this way can the resources needed to continue an FMEA program be secured. Finally, the method is always a cost factor – especially if you are really serious about involving all the stakeholders who play a significant role in the product and process designs being studied. Typically, FMEA teams include designers, analysts, process control engineers, manufacturing engineers, customer service personnel and managers. In addition, there are product team members from the operational value chain. For example, from pre-series production. In other words, workers who have installed the parts in question and are therefore most familiar with potential quality problems. In order to get all these stakeholders around the same table, it is essential to be able to demonstrate as reliably as possible what added value comparable FMEA projects have already achieved.

Leverage existing knowledge

It is not only the justification of the analysis effort that speaks for the implementation of performance measurement. The charm of a meaningful documentation of the results also lies in the fact that it serves as a reference for all comparable FMEA projects. The more quality problems are comprehensively known and the associated prevention measures can be researched, the more effectively repeat failures in related process and product designs can be ruled out.

This calls for the unlimited reusability of previous investigation results. A demand that is now also made by the industry standard AIAG & VDA FMEA, which has been published jointly by the two associations since 2019 and has since become the most important guideline, even outside the automotive industry, when it comes to establishing a functioning FMEA regime.

The standard is divided into seven substeps. These are:

- Planning & Preparation

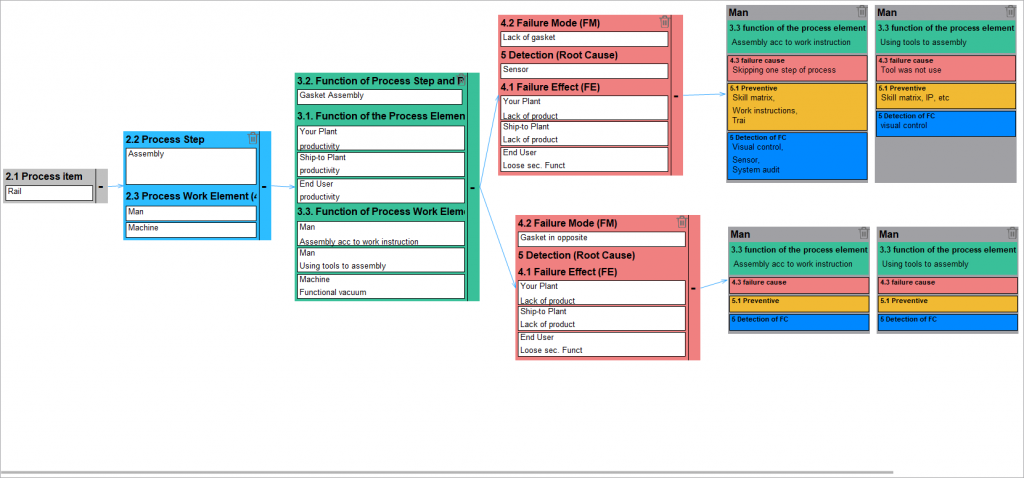

- Structure Analysis

- Function Analysis

- Failure Analysis

- Risk Analysis

- Optimization

- Result Documentation

QDA FMEA, the FMEA solution of our integrated eQMS software, follows this agenda. It provides users with standards-compliant templates and workflows to perform each of these sub-steps consistently. At the same time, it ensures that all FMEAs are stored in a central database so that all teams in the value chain can access them in an organized manner.

The consistent recording and processing logic promotes the comparability of the analyses. The same applies to the further use of the knowledge gained. For example, it is possible to process the FMEA knowledge in the QM documents based on it without having to record the data again. These documents include, for example, process flow diagrams, production control plans and inspection plans.

Don’t underestimate the need for change

From a purely technical point of view, all the prerequisites are in place for the widespread use of FMEAs outside the automotive industry. However, in order to apply the methodology successfully, some additional homework needs to be done. To understand what this means, it is worth taking a look at three important success factors that characterize well-functioning FMEA programs.

The first of these factors sounds simple, but in practice it is always a real challenge. It’s all about timing, and the most obvious way to do this is to start the analysis at the same time. FMEAs should start as close to the same time as planning projects for product development or process adjustments. This is the only way the analyses can develop their full predictive power. A more retrospective approach, on the other hand, always has the disadvantage that the measures derived from it always lag behind reality. In addition, there is a risk that such ex-post measures will lead to significantly higher implementation costs than an analysis carried out in parallel with the actual development project.

A sense of proportion is required. Especially at the beginning of engineering projects, when quality planning is not necessarily what the development teams strive for the most. With this in mind, the focus of the risk analysis should be set appropriately. The more precisely the scope is drawn, the more directly the stakeholders will see themselves in the FMEA and the more likely they will be to actively contribute to its success.

Really put your finger in the wound(s)

In practice, FMEA is assigned to and controlled by the development department. In many larger companies, quality planners share the responsibility. However, it is also a good idea to delegate the practical execution of the analysis to an independent third party. Preferably, this should be someone who has not had any contact with the actual subject of the analysis. The only important thing is that he or she is familiar with the method. This is the second important success factor for truly meaningful analyses. The fewer preconceived notions the methodologist has about how the process to be analyzed should work in practice, the greater the likelihood that he or she will ask the questions that really matter.

On the other hand, if you have an insider-only team, you run the risk of not being critical enough about some of the most important risks. After all, many quality defects have causes that seem too trivial to be seriously considered when designing new products and processes. An external facilitator does not have this bias. He or she can therefore question everything and enable the team to seriously address all relevant risks.

Never sit back

In principle, a Failure Mode and Effects Analysis is never finished. FMEAs do not even claim to ever be finished. They are living documents that must be continually updated. With new insights that come from production and assembly or from the field. All of this feedback must be evaluated in a timely manner so that previous actions can be adjusted or additional precautions can be taken. This is the third key success factor to consider when setting up an effective FMEA program.

Ultimately, FMEAs will continue to evolve as long as the product and process lifecycles for which they were designed continue to evolve. This provides companies with a highly effective tool for realizing the potential of continuous process improvement.